Last month, on the week of the fifth anniversary of the Paris Climate Agreement, Prime Minister Trudeau unveiled an ambitious plan for Canada to take more aggressive action on climate change.

The new plan, titled “A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy,” will build upon the 2016 Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change and put Canada on track to exceed its 2030 Paris Agreement reduction goal of 30% below 2005 GHG emission levels by as much as 10%. It is comprised of five pillars, one of which is an increase in the national carbon tax.

In 2018 the government of Canada passed the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GHGPPA), which required all jurisdictions to establish a pollution pricing scheme for fuel and industrial emissions that met federal standards and price minimums per tonne. The initial price was set at $20 per tonne of CO2 in 2019, with an annual increase of $10 every year until 2022. Under the new Plan, however, the annual increase would become $15 per year starting in 2023 until the carbon tax reaches $170 per tonne by 2030.

Given the flexibility provided in the GHGPPA, any province or territory could design its own carbon pricing system that was tailored to local interests, or they could opt (partially or fully) into a standardized federal pricing system. The federal pricing system is composed of two parts: a regulatory fuel charge for anyone who consumes fossil fuels like gasoline or natural gas, and a performance-based system for industries known as the Output-Based Pricing System.

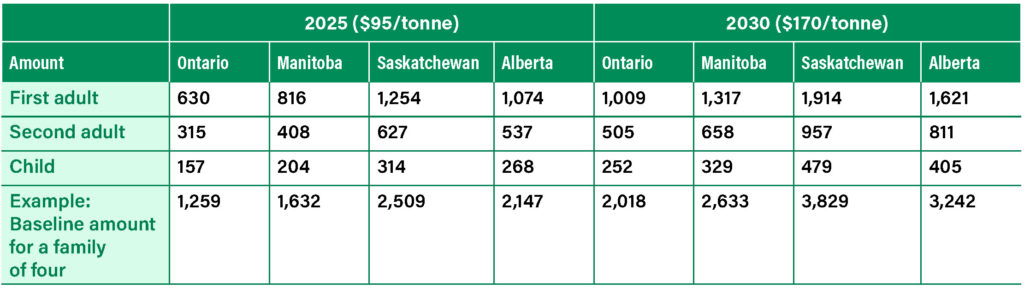

The intent of the federal pricing system is to be revenue neutral, with all proceeds given to individuals, families, and businesses through direct payments and other climate beneficial programs. Direct payments are not dependent on a household’s carbon footprint, and the hope is that the majority of households receive more in payments than they will face in costs each year. Below are estimated figures of what households in jurisdictions under the federal pricing system can expect to receive with the increased rate by 2025 and 2030.

Figure taken from A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy

As of now, five of the thirteen Canadian provinces and territories have opted into the federal pricing system to cover both fuel and industrial emissions. The eight remaining jurisdictions have either designed their own carbon pricing system, or they have opted into a combination of their own and the federal system. Most of the provincial systems mimic the structure of the federal pricing system (i.e., fuel charge and performance-based systems), however Quebec and Nova Scotia have instituted a cap-and-trade mechanism.

Quebec is also the only Canadian province that has a carbon pricing system linked with another entity (though Ontario joined them temporarily). Initially established in 2013, the Quebec cap-and-trade system was linked to California’s cap-and-trade system in 2014 as part of the Western Climate Initiative. This linkage allows for entities to trade allowances with one another across systems and has since created the largest carbon market in North America and the first between sub-national governments in different countries.

And although the GHGPPA has been successful in establishing a price on carbon throughout Canada, it has not come without opposition. Currently, the Supreme Court of Canada is deciding whether the federal price on carbon, as set by the GHGPPA, is constitutional. The Court has heard arguments from Quebec, New Brunswick, Manitoba, and other jurisdictions that acknowledge the need for climate action but are against the notion that the federal government can institute national standards to apply to all provinces and territories. The court adjourned in September 2020 and is expected to take several months before announcing a final ruling.

Despite the outcome, Prime Minister Trudeau and the federal government are positioning Canada as a leader on climate action by increasing ambition and action through targeted measures that go beyond just a price on carbon, particularly in North America. Though the United States is a couple weeks away from a new president, one that has pledged to take immediate action on climate change, it has fallen sharply on the world stage due to lack of action from the administration of the past four years. President-elect Biden has said he will have the country rejoin the Paris Agreement on day one of his presidency and propose new reduction targets, including net zero emissions by 2050.

It is unclear if a price on carbon will be included in the actions taken by the upcoming Biden administration, but with Canada, key states in the US, and Mexico implementing their own scheme, it may be a topic that is considered. And as the world consider a green recovery post-pandemic, Canada provides a good example that the US and other countries and local governments can follow if we hope to limit warming to 1.5 degrees by 2030.